Robert Nye,“The Culture of the Sword: Manliness and Fencing in the Third Republic” from Masculinity and Male Codes of Honor in Modern France (1)

The Glorification of Dueling

Perhaps the most popular novel of the early Third Republic was Georges Ohnet's Le Maitre des forges (The Ironmaster), first published in 1882, and in its 181st edition in 1884. Though not a writer of the first rank, Ohnet achieved a considerable following for his works by treating subjects of contemporary interest and employing the formulas for literary success of his day. His melodramatic play of the same title was a succés fou [wild success] in 1883, earning the plaudits "moving" and "true" from the fashionable critic Francisque Sarcey.1 Ohnet's novel is interesting to me because it displays the social and cultural implications of male honor more fully than any literary production in the era of the fledgling republic, in terms that spoke directly to the immediate concerns of its readers.

The hero of Ohnet's story is Philippe Derblay, a bourgeois of early middle age who has accumulated a fortune by reviving the failed ironworks he inherited from his father. Educated as an engineer at the prestigious Ecole Poly technique, Derblay was a hero in the war of 1870, "dark and male" with great personal courage and a distinctly unbourgeois taste for hunting and firearms. 2 All that is lacking in his worthy and productive world is a wife.

Philippe falls in love with a young aristocratic lady of the neighborhood, Claire de Branlieu, whose mother sees in Derblay the kind of match that noble families with good names but scarce resources made frequently in the nineteenth century. Claire's brother, Octave, regards Derblay as the wave of the future and hopes that the alliance of their families will make an "aristocracy" in the "new democracy," uniting those qualities that make a nation great: "past glories and progress in the present." 3 Alas, Claire is still pining for her childhood companion the callous Duke de Bligny, a diplomat whose dissolute ways and gambling have "marked and hardened" him, making him an unsuitable match.

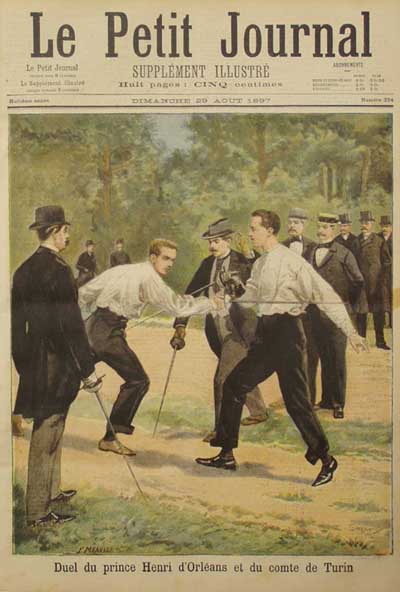

Duel of Prince Henri d'Orleans and the Count of Turin, Petit Journal, 1897

unconsummated. Crushed by her disdain, the saintly Derblay treats her with tenderness and consideration, but is too gallant to demand his marital rights. By degrees, his generosity, self-control, and moral superiority win her grudging admiration, if not her love. She recognizes that men like him are the "dominant force of the century," becomes his helpmeet in the business, and begins to regret her pride.

unconsummated. Crushed by her disdain, the saintly Derblay treats her with tenderness and consideration, but is too gallant to demand his marital rights. By degrees, his generosity, self-control, and moral superiority win her grudging admiration, if not her love. She recognizes that men like him are the "dominant force of the century," becomes his helpmeet in the business, and begins to regret her pride.